Why are there so many vacant houses in Baltimore City?

Baltimore’s vacant housing crisis is the result of a long timeline shaped by population loss, economic decline, discriminatory policies, and disinvestment—here’s how it happened.

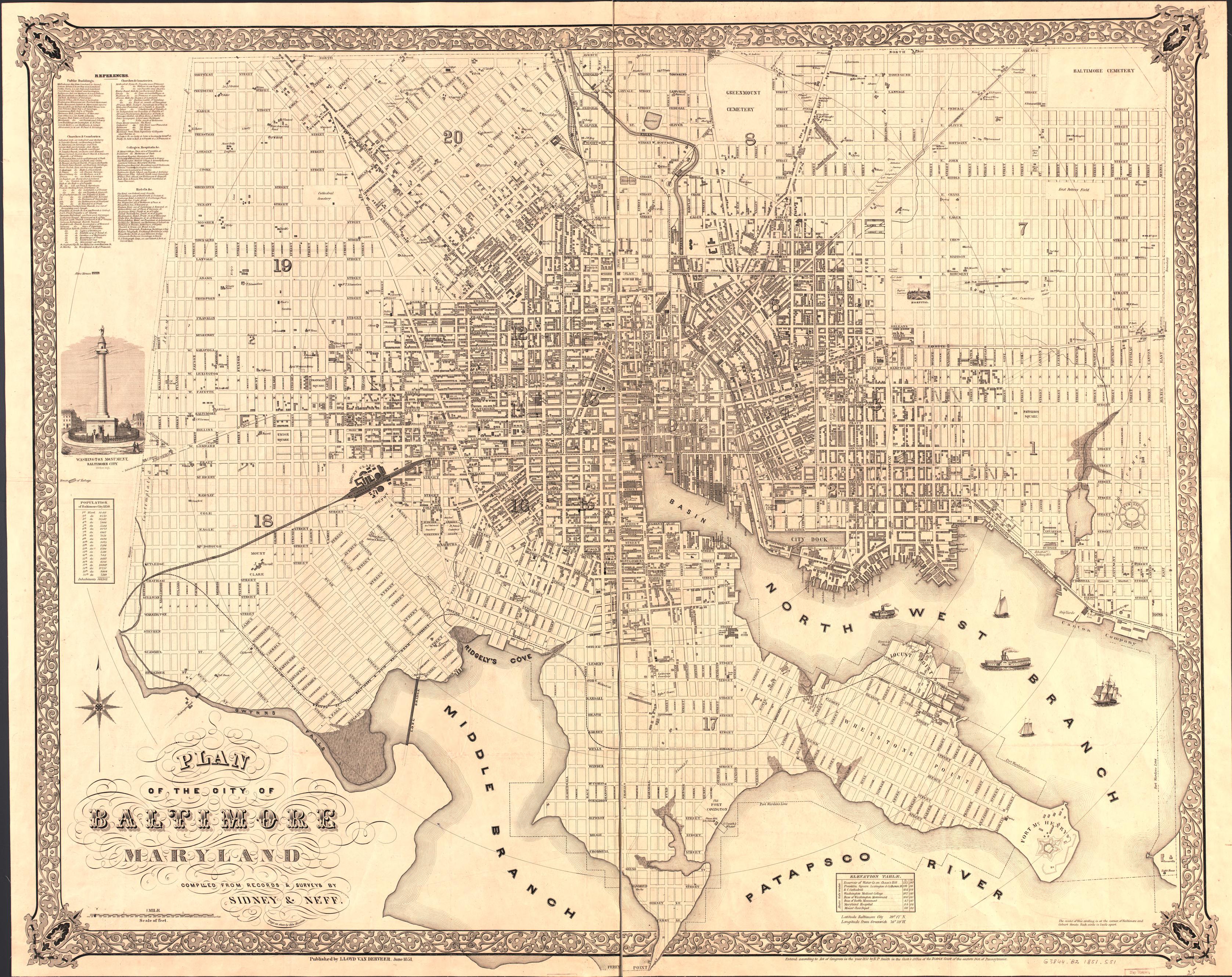

1790–1850

Early Foundations

Baltimore’s population grew from 13,500 in 1790 to 210,646 in 1850, including over 25,000 free Black residents—the largest such population in the U.S. This vibrant free black community coexisted with enslaved people, fostering economic mobility and resistance to slavery. Frederick Douglass described Baltimore as offering urban slaves a degree of autonomy unheard of on the plantations.

1851

City-County Split

Baltimore City separated from Baltimore County in 1851, creating distinct governance structures. This division later contributed to suburbanization trends that exacerbated racial and economic disparities between city and county residents.

1910–1917

Segregation Laws Begin

In 1910, Baltimore passed the nation’s first residential segregation ordinance, prohibiting Black residents from moving into majority-white blocks (and vice versa). Although overturned by Buchanan v. Warley in 1917, racial covenants and real estate practices continued to enforce segregation.

1910–1940

The Great Migration

During the Great Migration (1910–1940), thousands of African Americans moved to Baltimore in search of industrial jobs and to escape the violence of Jim Crow. The Black population doubled during this period, growing from 88,000 in 1910 to over 170,000 in 1940. Migrants faced overcrowding and systemic discrimination in housing and employment.

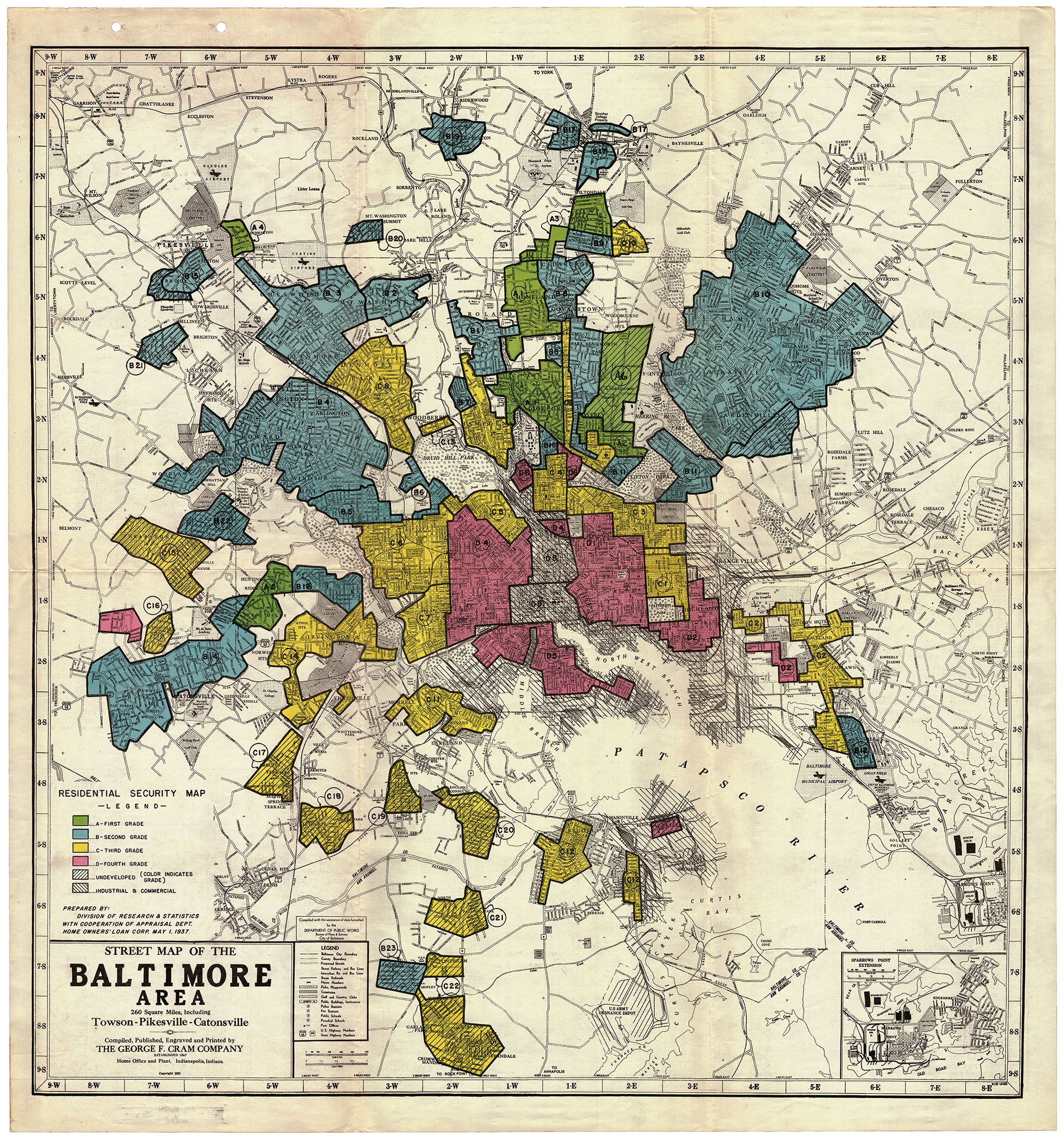

1930s–1940s

Redlining and Racial Discrimination

Federal housing policies in the 1930s and 1940s institutionalized racial segregation through practices like redlining. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) required developers to include racially restrictive covenants in new subdivisions to secure financing, effectively excluding Black families from suburban developments. Neighborhoods such as Roland Park and Guilford, originally developed earlier but reinforced by these policies, came to symbolize this exclusivity. As a result, Black families were denied homeownership and investment opportunities, fueling systemic inequality and contributing to neighborhood disinvestment and vacancy.

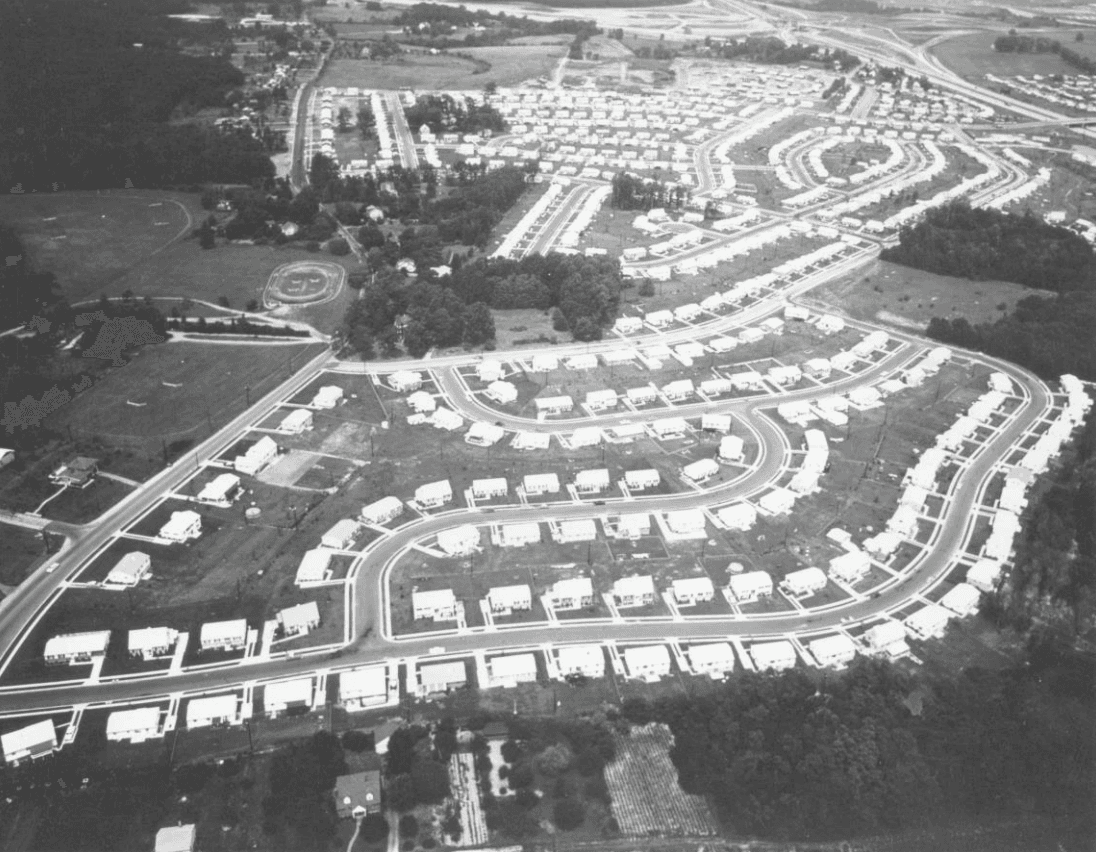

1940s–1950s

Suburbanization, Public Housing, and the GI Bill

Suburbanization accelerated after World War II as white families benefited from FHA-backed loans and GI Bill provisions that guaranteed mortgages for returning veterans. Black veterans, however, were systematically excluded from these benefits due to discriminatory practices by Veterans Administration counselors and private lenders. Even those who qualified faced barriers such as racial covenants and segregated schools, preventing them from moving into suburban developments. Black families were confined to segregated public housing projects such as McCulloh Homes or Cherry Hill, and deliberately isolated from white neighborhoods. Blockbusting further destabilized urban Black neighborhoods by exploiting fears of integration to manipulate housing markets.

1950s–1970s

Highway Displacement and Community Resistance

The "Highway to Nowhere," or I-170, was designed to connect downtown Baltimore to suburban interstates but disproportionately targeted Black neighborhoods in West Baltimore for demolition. Construction in the late 1960s destroyed 20 city blocks, including 971 homes, 62 businesses, and a school, displacing more than 1,500 residents from middle-class Black communities. Though the freeway was never completed, neighborhoods like Harlem Park and Franklin-Mulberry were devastated, and the destruction from eminent domain and demolition left lasting physical and symbolic barriers that still hinder economic growth and connectivity.

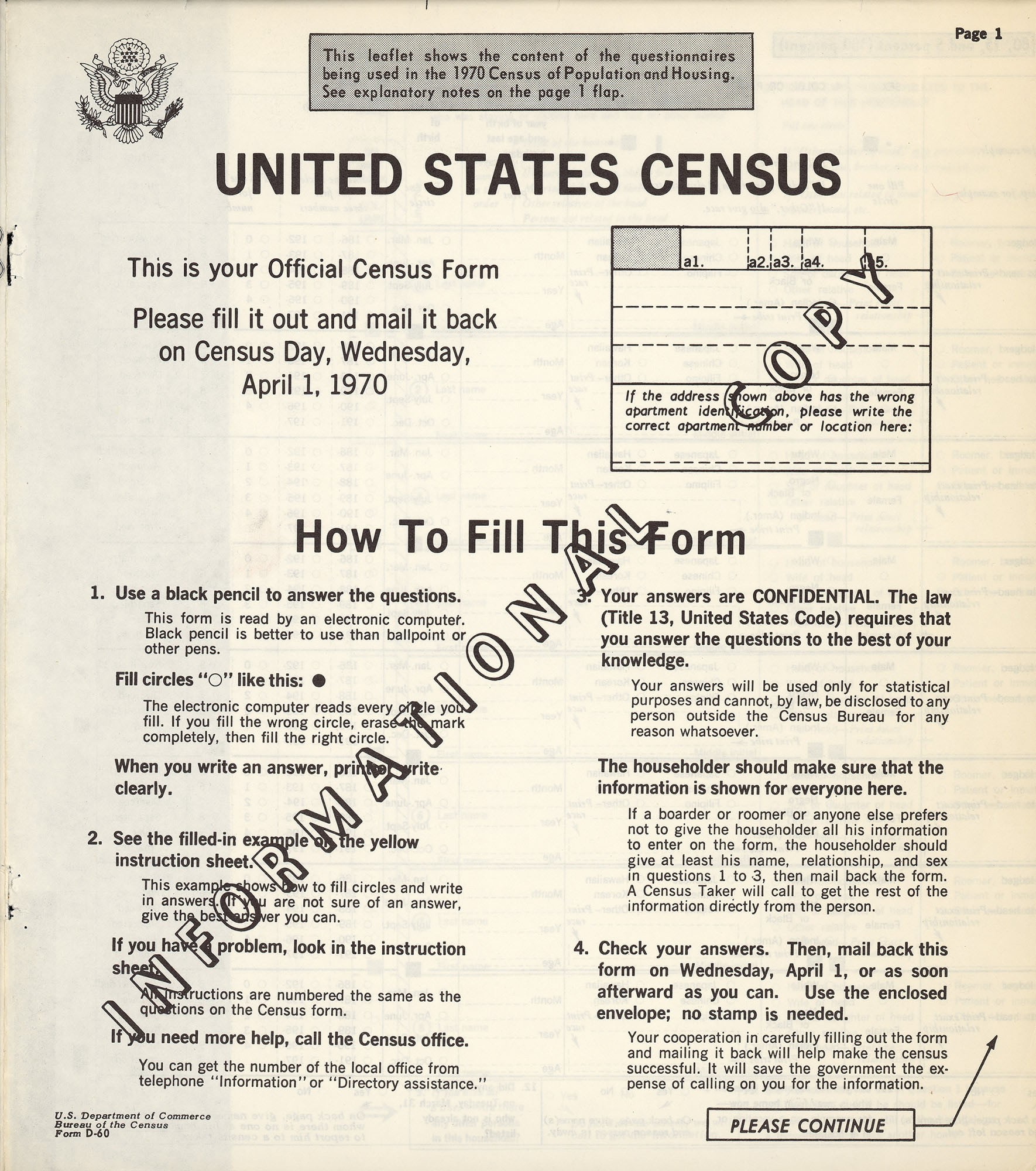

1960–1970

Majority Black City

In the late 1960s, Baltimore’s Black population surged due to the Great Migration and wartime industrial jobs, reaching nearly half of the city’s population by 1970. This demographic shift marked Baltimore’s transition to a majority-Black city.

1970s–1980s

Community Organizing

In the late 1970s, groups like BUILD (Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development), founded in 1977, mobilized against housing discrimination and systemic disinvestment in Baltimore neighborhoods. This work included direct pressure on banks to lend in marginalized areas and on corporations and public officials to create a Commonwealth Agreement that would increase opportunities for young people, jobs, and more. BUILD’s efforts played a significant role in targeting investment and neighborhood development in historically disinvested neighborhoods through the creation of hundreds of Nehemiah homes across Baltimore. These new owner-occupied homes created wealth and affordable homeownership opportunities for families. BUILD’s efforts also helped secure federal and state support for community investment, particularly in historically disinvested areas.

1980s–1990s

Decline & Disinvestment

During the 1980s and 1990s, Baltimore experienced severe economic and social decline, driven by white flight, deindustrialization, and the crack cocaine epidemic. The closure of major employers such as Bethlehem Steel and General Motors eliminated thousands of industrial jobs, disproportionately affecting Black residents and exacerbating poverty. Federal disinvestment under Reagan-era policies further deteriorated urban conditions, leaving Baltimore with fewer resources to address its growing challenges.

The crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s brought devastating consequences to Baltimore’s communities, fueling violent crime and addiction. By the mid-1990s, Baltimore had one of the highest homicide rates in the nation, peaking at 353 murders in 1993. This violence coincided with a dramatic increase in vacant properties—estimated at over 40,000 by the late 1990s—as population loss accelerated. Entire neighborhoods were hollowed out, leaving visible scars that remain today. Baltimore’s struggles during this period reflected broader trends in urban America but were compounded by systemic racial inequities and longstanding disinvestment in what became known as the ‘black butterfly.’

Early 2000s

Housing Boom and Bust

Baltimore experienced a sharp rise in housing prices in the early 2000s. Developers and investors flooded the market, often targeting low-income neighborhoods with subprime loans that carried high risks for borrowers. In 2008, the collapse of the housing bubble triggered the subprime mortgage crisis, which disproportionately affected Black homeowners in Baltimore. Foreclosures skyrocketed by more than 60%, with many families losing their homes to predatory lending practices.

The crisis devastated Baltimore’s housing stock, leaving thousands of properties abandoned and exacerbating vacancy rates across the city. Between 2008 and 2010, foreclosures cost Baltimore residents over $1.5 billion in lost equity, while the city lost $13.6 million in property taxes due to vacant homes. Public housing units were also being dismantled during this period without adequate replacement housing. The combined effects of foreclosure, disinvestment, and public housing reductions deepened economic inequality and left lasting wounds for Baltimore’s neighborhoods.

2020 to 2023

A Bold Strategy & Historic Re-investment

As of the 2020 Census, Baltimore City’s population was 585,708 and it continued to decline through 2024. In 2020, there were 15,748 vacant properties. Baltimore DHCD begins implementing a comprehensive framework for neighborhood investment.

Mayor Scott acknowledged that Baltimore’s vacant property problem persists because of a lack of capital, not capability. He realized there needed to be a significant change in how the city approached this issue and set out to make it happen.

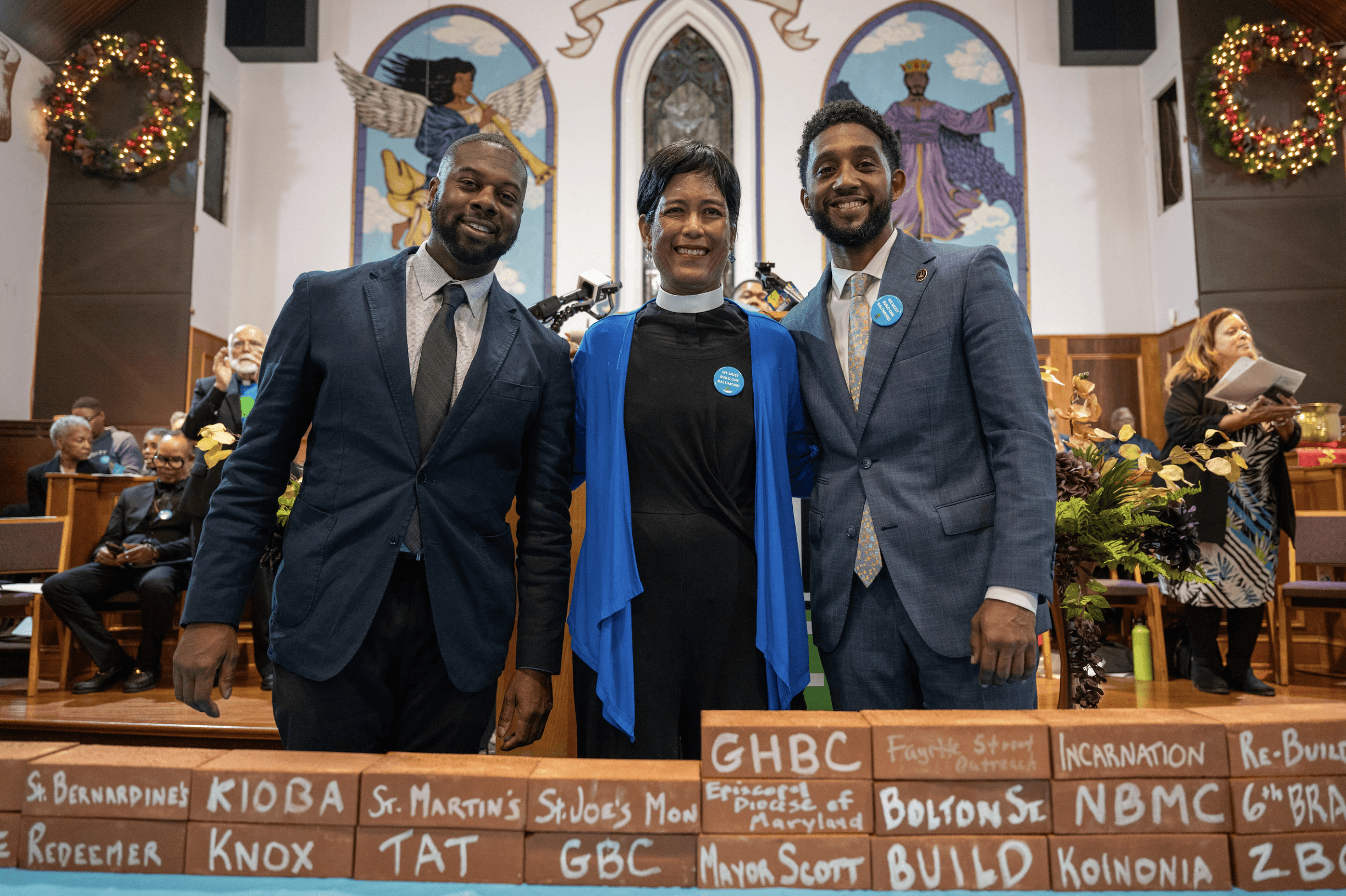

In December 2023 Mayor Scott, in partnership with the Greater Baltimore Committee, and BUILD announced a $3 billion capital strategy and 15-year vision to end the vacant property crisis in Baltimore City once and for all. This included a framework to reshape investment from the state, philanthropic partners, and the business community, as well as the announcement of the nation’s first non-contiguous TIF.

2024

Governor Moore announces Baltimore Vacants Reinvestment Initiative

Building on the 2023 announcement, Governor Wes Moore signed an Executive Order, launching the "Reinvest Baltimore" initiative to solidify the state’s role in the effort and committed to transforming at least 5,000 vacant properties in Baltimore over five years. The order created the Baltimore Vacants Reinvestment Council to coordinate efforts across state, local, nonprofit, and private sectors. With an annual $50 million investment, the initiative marked a historic commitment to revitalizing neighborhoods, creating affordable housing, and spurring economic development in Baltimore City.

2025

Baltimore Sees the Impacts of These New Investments

This new approach and the unprecedented partnership that drives it is already starting to make an impact under Mayor Scott’s leadership, violent crime has been declining at historic rates, the city saw its first population growth since 2014, and the number of vacant properties has been reduced by more than 18%.

This year TIF dollars are in the process of hitting the ground in the initial offering to support construction in the City-Wide Affordable Housing Development District. DHCD continues to implement the 2025 priority blocks working with community leaders, developers, and residents to support the community’s vision for their neighborhoods.